Filtration and Drying of IonoSolv Lignin Extraction: Analyzing the Effects of Pre-Filtration Agitation and Drying Conditions

Abstract

This study focused on the investigation of the changes in physical appearance and chemical structural changes under various drying environments and pre-stirring filtration during the vacuum filtration and drying process of spruce black liquor manufactured by the IonoSolv process. In the pre-stirring filtration process, the particle size and zeta potential were measured by particle size analysis, and the effect of lignin seeding was examined. In the drying process of lignin, 1H-13C 2D Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (2D HSQC) NMR spectroscopy was employed to observe the physical and chemical changes under static and dynamic drying environments of various temperatures and drying methods. Through this study, the inefficiency of stirring and the potential of lignin seeding is revealed. Moreover, it is possible to ascertain the effects of high temperatures and different drying methodologies on the changes in molecular structure and particle size of lignin.

Introduction

Literature

Research Question

1.

Filtration Efficiency:

•

What is the effect of pre-filtration agitation on particle size distribution, zeta potential, and filtration efficiency during the IonoSolv process?

•

How does lignin seeding contribute to filter cake formation and enhance filtration performance?

2.

Drying Conditions:

•

In what ways do different drying methods (e.g., oven, vacuum, freeze-drying, and dynamic drying) impact the chemical composition and physical properties of lignin?

•

What specific structural modifications, such as condensation and polymerization, occur in lignin under varying drying conditions?

3.

Process Optimization:

•

To what extent can optimized agitation and drying protocols improve lignin recovery, structural integrity, and overall yield?

•

How do the chemical and physical changes induced by filtration and drying processes influence lignin’s functionality for downstream industrial applications?

Aim of the Research

The primary aim of this research is to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the filtration and drying stages within the IonoSolv lignin extraction process, focusing on spruce black liquor. Specifically, this study seeks to:

1.

Investigate the influence of pre-filtration agitation and lignin seeding on filtration efficiency, particle size distribution, and filter cake formation.

2.

Examine the effects of various drying techniques on the structural integrity, chemical composition, and physicochemical properties of lignin.

3.

Develop standardized protocols and optimization strategies to improve lignin recovery, quality, and its suitability for industrial-scale applications.

Significance

This research is pivotal in advancing the IonoSolv process for lignin extraction by addressing key challenges in filtration and drying. By optimizing these critical stages, the study enhances the efficiency and scalability of lignin recovery while preserving its structural and functional properties. The findings contribute to the development of standardized protocols that bridge the gap between laboratory experiments and industrial applications, promoting consistent and sustainable processes. Additionally, this work supports the broader goal of a circular bioeconomy by maximizing resource utilization and enabling the production of high-value bio-based materials, aligning with global sustainability initiatives.

Methodology

1. Experimental Design

Materials and Sample Preparation

•

Lignin Source: Norway spruce black liquor was procured from Ionosolv pilot-scale biorefinery facility. The lignin-rich liquor was pretreated with protic ionic liquids ([HSO4]−), synthesized via acid-base neutralization of sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) and N,N,N-Dimethylbutylammonium (DMBA), and adjusted to 20 wt% water content.

•

Precipitation and Seeding: Lignin precipitation was achieved through antisolvent addition (deionized water) under controlled magnetic stirring. For lignin seeding experiments, freeze-dried lignin was added during the precipitation process to facilitate particle aggregation.

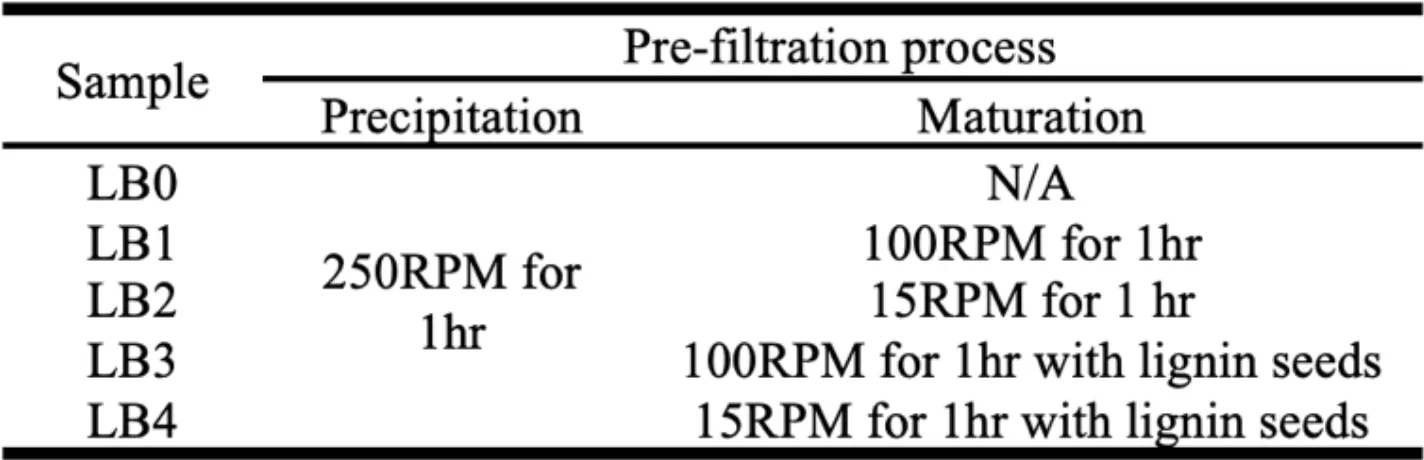

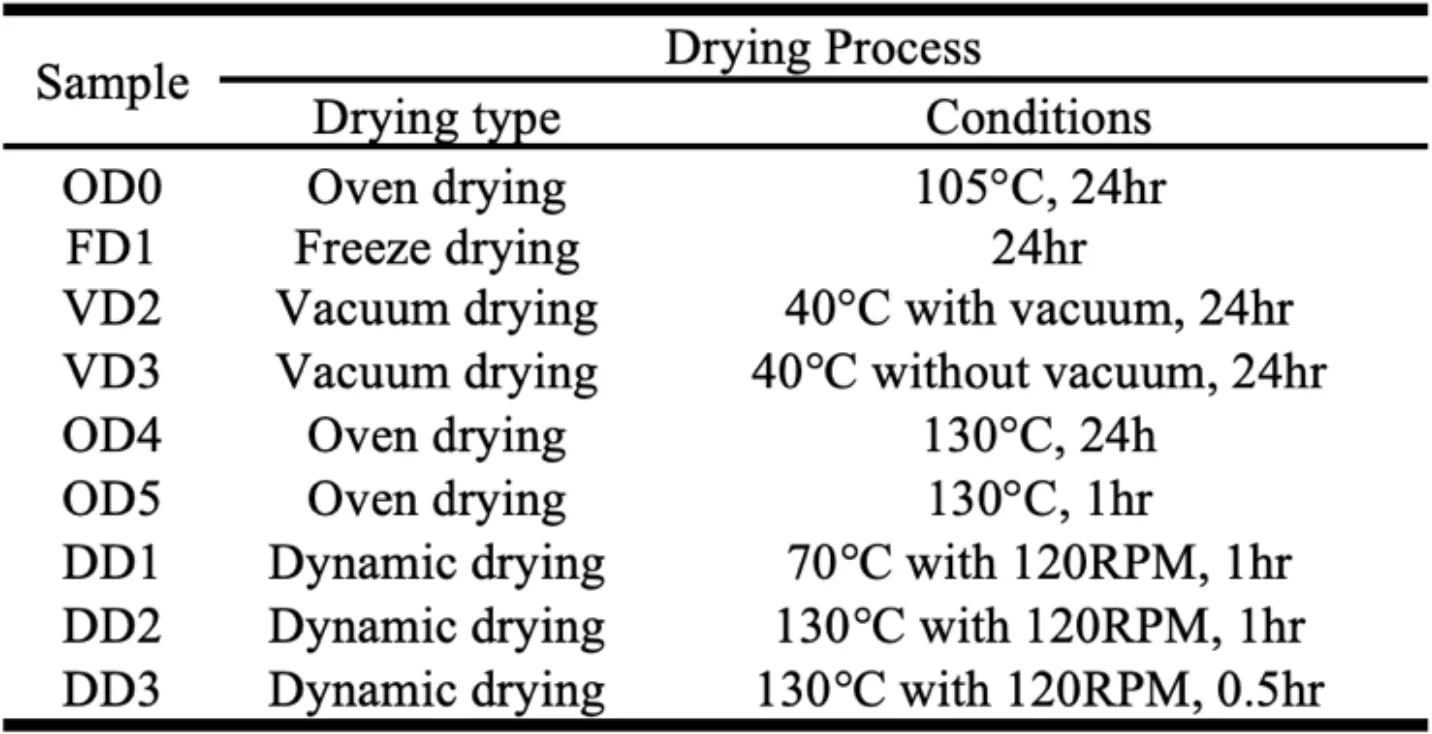

Table 1 Sample Preparation for precipitation and maturation process with different magnetic stirring speeds using Ionosolv Black liquor (LB) sample

Filtration and Washing

•

Filtration Setup: A borosilicate glass vacuum filtration apparatus with a 10 µm pore size sand core filter was employed under 10 mbar vacuum pressure. The lignin-rich ionic liquid suspension was subjected to a 1-hour maturation period under varying stirring speeds (Table 1).

•

Filtration Protocol: Samples were filtered in three stages, with refiltration performed until the filtrate exhibited a light-yellow color. Filtration time was recorded for each stage.

•

Washing: Residual ionic liquids were removed from the wet lignin cake by sequential washing with deionized water until the pH of the filtrate stabilized at 4. The washed lignin was subsequently freeze-dried to obtain a purified product.

Table 2 Different types and conditions of the drying process for extracted Ionsolv Black liquor sample

Drying Processes

•

Static Drying Methods:

◦

Oven Drying: Conducted at 105°C and 130°C for 1–24 hours.

◦

Vacuum Drying: Performed at 40°C under vacuum for 24 hours.

◦

Freeze-Drying: Samples were freeze-dried for 24 hours.

•

Dynamic Drying:

◦

Conducted on a magnetic stirring plate at 70°C and 130°C for durations ranging from 0.5 to 1 hour. Temperature was continuously monitored using an infrared thermometer.

2. Data Analysis

Filtration Performance

•

Filtration Efficiency: Filtration time and lignin yield were calculated for seeded and unseeded samples. Lignin yield was determined by the dry weight of the lignin cake after freeze-drying.

•

Particle Size Distribution: Multi-Angle Dynamic Light Scattering (MADLS) was employed to measure the average particle size and polydispersity index.

•

Zeta Potential Analysis: Surface charge of lignin particles was quantified using a Litesizer DLS500, providing insights into colloidal stability.

Fig. Vacuum filtration setup used for lignin extraction and purification; Anton Paar PSA 1190 instrument for particle size analysis; Anton Paar Litesizer DLS 500 for zeta potential and dynamic light scattering measurements.

Drying Effects on Lignin

•

Morphological Analysis:

◦

Optical microscopy was utilized to examine particle size distribution, aggregation, and granularity under static and dynamic drying conditions.

◦

Microscopic images were analyzed using ImageJ software for precise measurement of particle diameters.

•

Chemical Structural Analysis:

◦

2D HSQC NMR Spectroscopy: A Bruker Avance III 800 MHz spectrometer was employed to monitor structural alterations in lignin. The spectra were analyzed to detect functional group modifications in the aromatic (guaiacyl and syringyl) and aliphatic regions (β-O-4, β-β, and γ-OH linkages).

◦

Quantitative changes in methoxy groups, carboxylic acids, and phenolic hydroxyl groups were correlated to drying temperature and method.

Fig. Leica optical microscope used for morphological analysis of lignin particles; Bruker Avance Neo 800 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with an Ascend 800 cryomagnet, utilized for advanced 2D HSQC NMR spectroscopy to analyze lignin's chemical structure.

Result

1. Filtration Process Results

Impact of Agitation and Lignin Seeding:

•

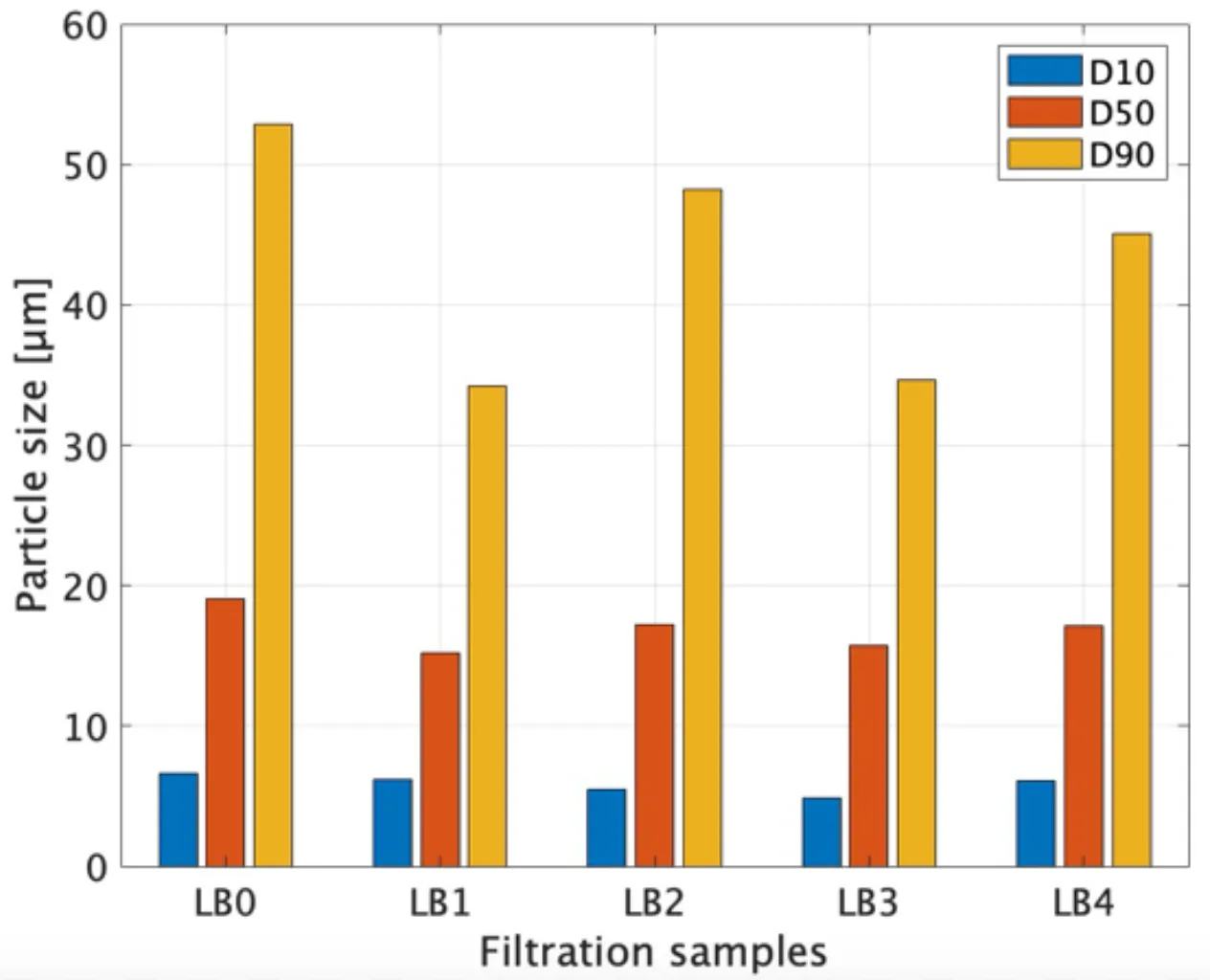

Pre-stirring increased uniformity and reduced lignin particle size. The process promoted filter cake formation, reducing filtration time (from 3 to 2 hours) while increasing lignin yield (from 2% to 2.7–3.2%).

•

Zeta potential analysis showed surface charge stability (-33.82 mV to -45.18 mV), supporting effective lignin dispersion.

Filtration Efficiency:

•

Lignin seeding enhanced lignin precipitation rates, forming compact, uniform filter cakes.

•

Gentle agitation was less effective due to lignin particle re-dispersion, especially at higher speeds.

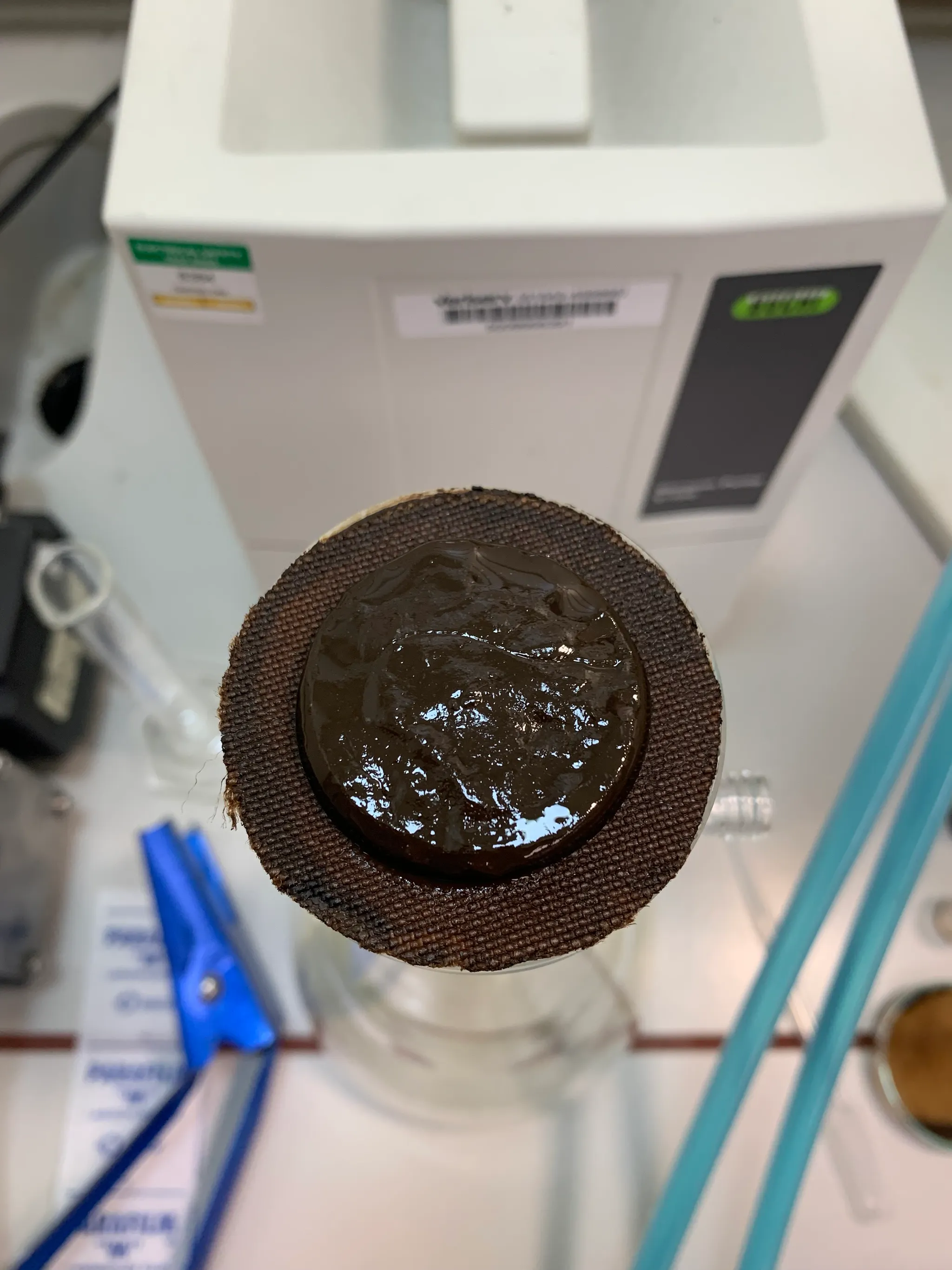

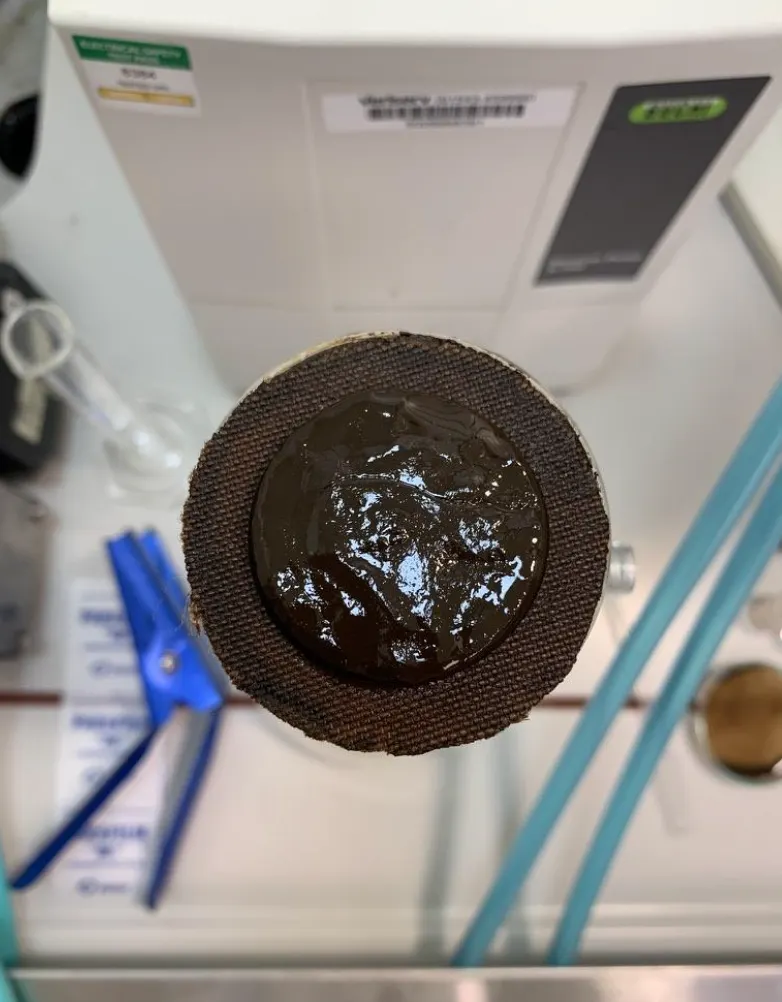

Fig. 3 (b) 25g of lignin filter cake after second filtration

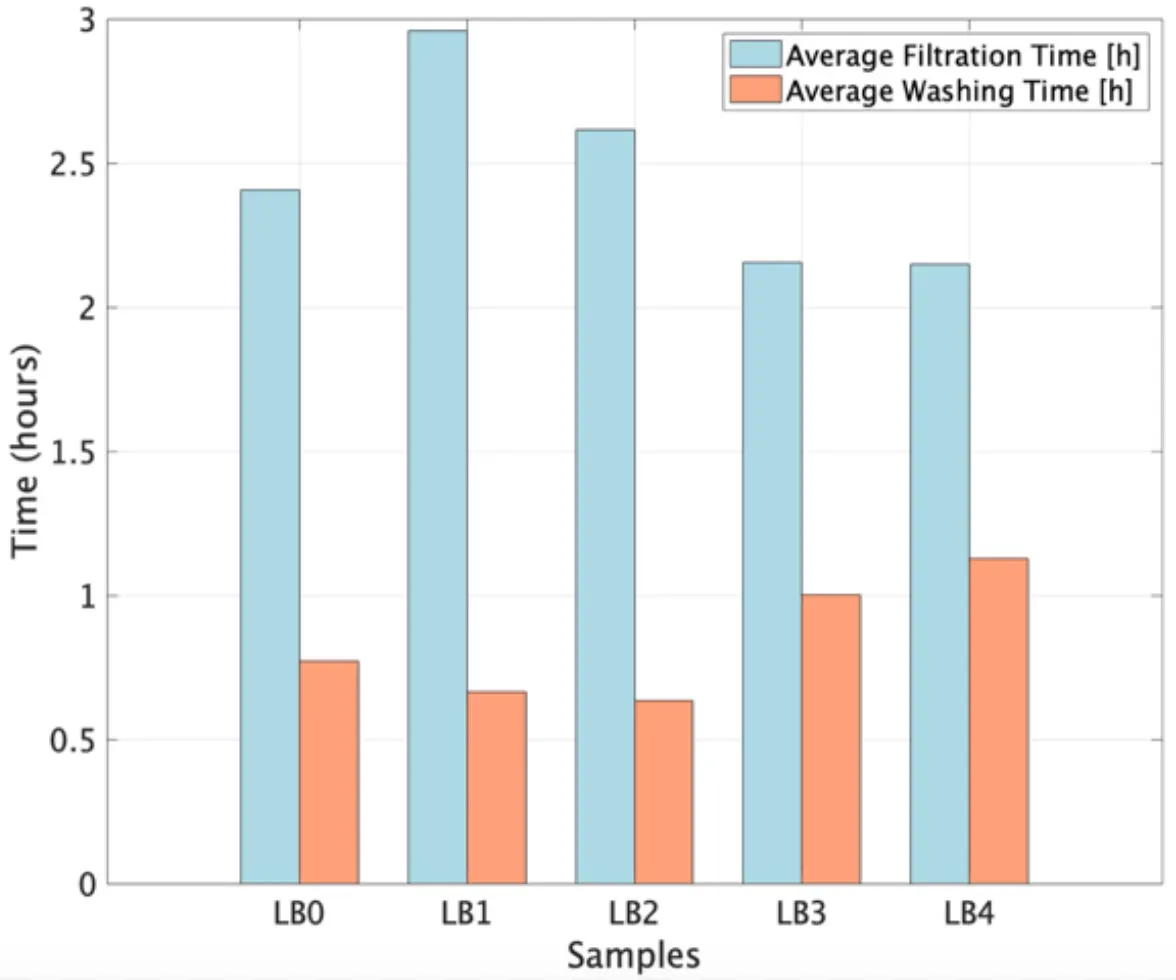

Fig. 4 Average filtration and washing time (hour) of each sample

Fig. 5 Particle size distribution D10, D50, and D90 corresponding to the percentages 10%, 50%, and 90% of filtered lignin samples (Anton Paar GmbH PSA 1190 instrument)

2. Drying Process Results

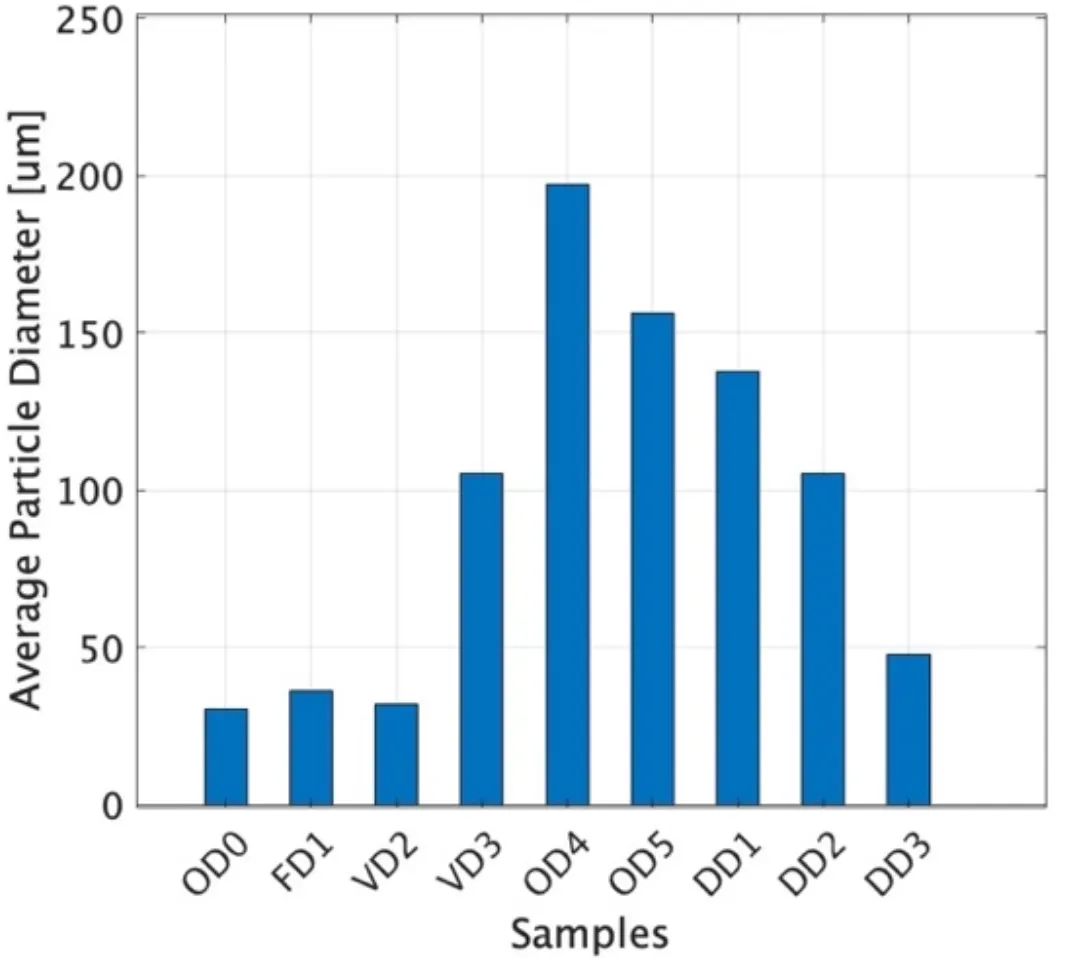

Fig. 8 Average Particle Diameter of Dried Lignin Samples: Oven-dried (OD), Freeze-dried (FD), Vacuum-dried (VD), and Dynamic-dried (DD)

Particle Size and Physical Appearance:

•

Oven drying at 105°C and freeze drying produced fine, uniform lignin particles.

•

Higher temperature oven drying (130°C) led to coarser, aggregated particles, while vacuum drying at 40°C resulted in irregular granularity.

•

Dynamic drying at elevated temperatures (70°C and 130°C) produced uneven particle distributions with fragmentation.

Chemical Structural Changes (via ¹H-¹³C 2D HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence) NMR):

•

Aromatic Region:

◦

Guaiacyl (G) and syringyl (S) units showed significant degradation under high-temperature and dynamic drying conditions (130°C), resulting in reduced peak intensity and structural alteration.

◦

Freeze drying preserved aromatic structures with minimal condensation reactions.

•

Aliphatic Region:

◦

Methoxyl and β-O-4 linkages were prominent in low-temperature drying (freeze or vacuum drying), while higher temperatures caused ether bond cleavage, reducing aliphatic structures.

◦

Dynamic drying conditions accelerated side-chain degradation and condensation reactions.

3. General Observations

Filtration Enhancements:

•

Lignin seeding increased process efficiency by promoting better particle interactions and compact filter cake formation.

•

High agitation speeds negatively impacted particle size uniformity.

Drying Conditions:

•

High-temperature drying (≥130°C) resulted in increased lignin condensation and reduced aliphatic integrity due to enhanced C-C and C-O-C bond formation.

•

Freeze drying emerged as the optimal method for preserving lignin's structural integrity.

Discussion

Key Findings and Comparisons with Literature

This study explored the impact of pre-filtration agitation and various drying conditions on the physical and chemical properties of lignin extracted via the IonoSolv process. The results demonstrated significant effects of operational parameters on lignin recovery, structural integrity, and application potential.

•

Pre-Filtration Agitation and Lignin Seeding:

The introduction of pre-filtration agitation significantly improved particle size uniformity and reduced overall filtration time. Calculations revealed that pre-agitation and lignin seeding reduced filtration time by 10.73% and washing time by 17.91% compared to the baseline condition (LB0). These findings align with Chambon et al., who emphasized the role of agitation in reducing mass transfer resistance and facilitating efficient lignin precipitation. The results also validate the hypothesis that lignin seeding promotes filter cake formation and improves downstream washing efficiency.

•

Drying Conditions and Physical Appearance:

Different drying techniques induced notable variations in lignin morphology. Freeze-drying produced fine, uniform particles with minimal aggregation, consistent with studies showing that low-temperature drying minimizes condensation reactions. Conversely, oven drying at higher temperatures (130°C) resulted in coarser particles, attributed to thermal decomposition and condensation reactions forming C-C and C-O-C bonds. This trend aligns with reports by Mazar et al., which observed significant structural changes in lignin under high-temperature drying.

•

Chemical Structural Changes:

The ¹H-¹³C HSQC NMR analysis revealed that freeze-drying preserved the aliphatic and aromatic structures of lignin, as indicated by well-defined guaiacyl (G) and syringyl (S) peaks. In contrast, oven drying at 130°C reduced peak intensity, signaling structural degradation. Dynamic drying exacerbated this degradation, particularly in the β-O-4 and β-β linkages, due to the combined effects of heat and agitation. These observations are consistent with Balakshin et al., who noted that high temperatures lead to cleavage of ether bonds and enhanced condensation reactions.

Analysis of Results and Logical Interpretation

•

The observed reduction in particle size with pre-agitation can be attributed to the shear forces generated during stirring, promoting uniform lignin precipitation. The success of lignin seeding in increasing yield and filtration efficiency highlights its potential for scaling up the IonoSolv process.

•

The stark differences in lignin morphology across drying methods underscore the sensitivity of lignin to thermal and physical stresses. Freeze-drying's ability to preserve lignin structure stems from its low-temperature, low-pressure environment, minimizing chemical reactions. In contrast, high-temperature drying accelerated lignin polymerization and structural rearrangement, as evidenced by the increased condensation signals in the NMR spectra.

•

Dynamic drying at 130°C caused pronounced structural degradation, likely due to the interplay between thermal energy and mechanical agitation. This suggests that controlled drying protocols are essential for maintaining the structural and functional integrity of lignin for industrial applications.

Limitations

This study was conducted at a laboratory scale, limiting its applicability to industrial processes where lignin behavior may differ significantly. The focus on specific drying methods and temperatures excluded other potentially effective techniques, such as spray drying or supercritical drying. Additionally, the reliance on ¹H-¹³C HSQC NMR without complementary techniques like 31P NMR or FTIR constrained the depth of chemical analysis. The exclusive use of Norway spruce black liquor as a biomass source limits the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, the study did not address energy consumption or cost implications, crucial factors for industrial implementation.

Further Research

Future studies should scale up the processes to industrial levels and explore additional drying techniques and intermediate temperature ranges. Advanced analytical methods, including 31P NMR and FTIR, should be employed for a more comprehensive chemical analysis. Expanding to various biomass types, such as hardwoods and agricultural residues, will validate the findings' universality. Additionally, incorporating energy and cost efficiency analyses will better assess the practical feasibility of the optimized processes.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of pre-agitation and lignin seeding in reducing processing times, achieving a 10.73% reduction in filtration time and a 17.91% reduction in washing time. Additionally, freeze-drying emerged as the most effective method for preserving lignin's structural and morphological integrity. High-temperature and dynamic drying methods, while efficient, introduced significant degradation risks.

Future advancements should focus on scaling up these optimizations, exploring diverse drying methods, and conducting more comprehensive analyses of cost and energy efficiency. These efforts will enhance the feasibility of lignin valorization in biorefinery applications and contribute to the development of a sustainable circular bioeconomy.